In many data-based sciences, such as digital art history or specialised historical IT, there is a debate about how to deal with sensitive content in the digital domain, what strategies are needed in this connection, and how these are compatible with the so-called FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) for research data. The academic discussion is accompanied by a public debate about sensitive language and about the use of racist and discriminatory terms and motifs in literature and the visual arts. Taking the example of (historical) photographs with sensitive content, this article discusses possible strategies for addressing the issue, starting with a discussion of the consequences of digitality for photographs. As such, the article presents an issue of current interest that needs to be discussed in connection with provenance research, too. The spring conference of the German Lost Art Foundation on the topic “Provenance Research & Photography” provides a suitable framework for this.

Non-publication is not a solution

Photographs are vital sources for provenance research since they bear witness to the origin of an object. The content of such photographs can be problematic if they depict racism, discrimination or colonial power structures. Even in the analogue world, dealing with sensitive content requires tact and an appreciation of the problems involved, but such demands are significantly heightened in the digital sphere.

The digitisation of photographic collections ensures their preservation, and if they are subsequently put online it means that (provenance) research can be conducted independently of time and place, helping to make photographs permanently accessible to a broad public. The digital format also allows the content to be edited and means photographs can be reproduced indefinitely. However, this also involves a loss of control over the further use of the photographs, which can subsequently be embedded in new contexts. Possible consequences include misuse for political purposes, for example, and also misinterpretation. What is more, transfer to the digital domain can lead to sensitive content being passed on without the necessary reflection, with the result that the images may continue to offend certain groups of people. This entails great responsibility, not only for database operators but also for data producers. Does this mean that photographs with sensitive content should not be posted online? In the author’s opinion, non-publication is not a solution; after all, photographs are important sources and evidence of historical facts. Not showing them could ultimately falsify history, too. So how might it be possible to address this issue appropriately?

Strategies for dealing with sensitive content

On 23 June 2023, the Forum Foto + Album organised a meeting on the topic “Strategies for dealing with sensitive content in photographs and albums”, focusing on strategies for publications and exhibition spaces. Here, the impact of photographic images is defused by means of visual interventions such as covering certain parts of the image or breaking an image down into individual parts. Another strategy is to deliberately not display a photograph, instead marking its absence by means of a blank space. These analogue processes can also be applied to the digital sphere.

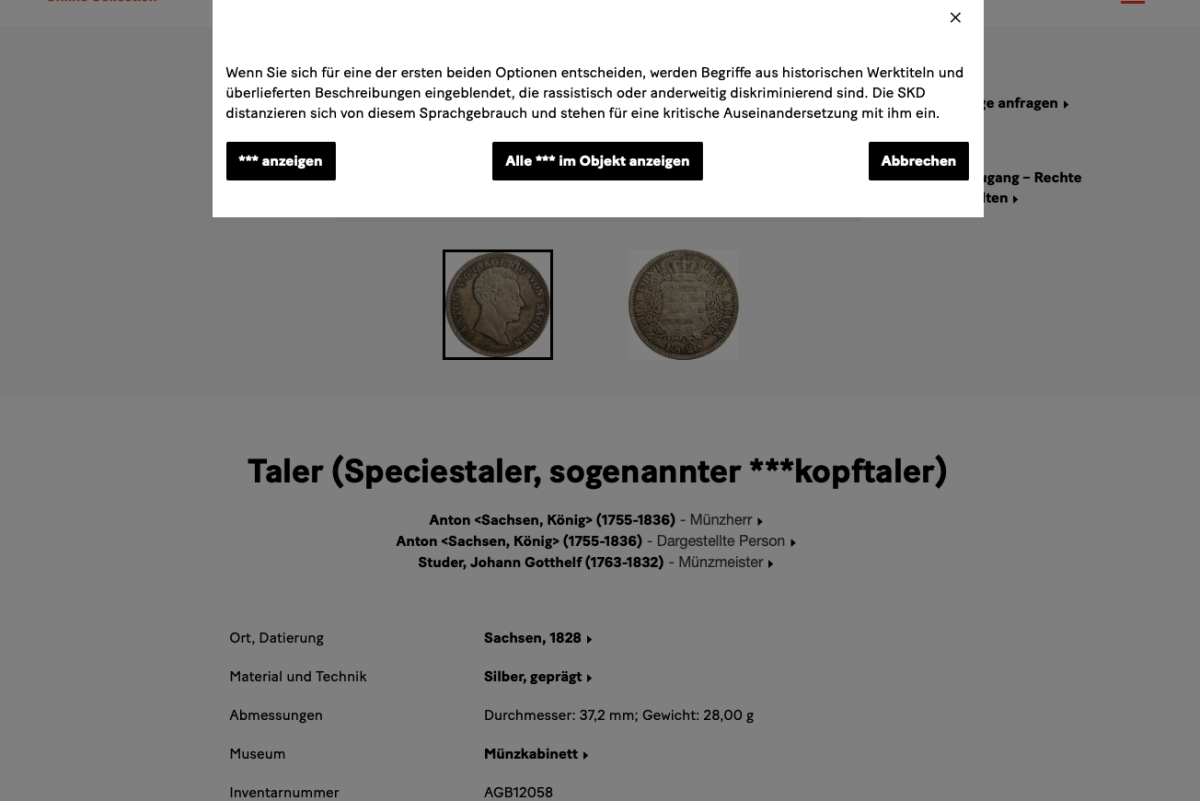

The Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (State Art Collections) have decided to hide racist and discriminatory terms in work titles and descriptions in their online collection and replace them with asterisks. Only on a second level can users decide to have the terms displayed (see figure). The Digital Benin database uses several strategies to highlight the problematic nature of some content. There is already a statement on the homepage that refers to “sensitive content”. The “Use of derogatory, racist and harmful language” page contains information about the use of offensive, racist or hurtful language. These also contain concrete suggestions on how problematic content can be dealt with. It's interesting that different categories are established for problematic language and different solutions are proposed for them. These solutions become visible in the object data: some words are replaced by visual blank spaces, others are marked by rectangles. When hovering over it, the warning “Sensitive Content Detected” appears and with a click it opens a pop-up with further information and linked content. Similar strategies could be used to present photographic holdings online. In computer science, for example, data sheets are proposed for data sets that are intended to promote transparency and responsibility. The data sheets contain questions that are assigned to different categories. For example, one category contains questions about legal and ethical considerations: Does the data set contain information that is considered sensitive or confidential or could it cause harm to people? Similarly, data sheets could be created for photographic assets that provide information about potential negative implications. Finally, other options would be conceivable, e.g. restricting access using authorization procedures.

Final Thoughts

The spring conference offers a suitable framework for exchange and discussion about possible strategies for dealing with sensitive content on the Internet. Affected groups of people must be included in the discussion and development when implementing digital strategies. Ultimately, the strategies should ensure data accessibility in accordance with the FAIR principles and the “Washington Principles”. The FAIR principles require, among other things, the accessibility of research data, although it is possible to restrict access to sensitive content as long as the access path remains traceable. Finally, in the context of provenance research on collection items from colonial contexts, the CARE principles (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics), which are intended to protect the interests of indigenous communities, must also be taken into account.

Sabine Lang is a research assistant in the Department of Digital Humanities and Social Studies of Friedrich Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg.

https://www.dhss.phil.fau.de/person/dr-sabine-lang

This blog post is the first of a small series of articles that will be published in conjunction with the spring conference of the German Lost Art Foundation on the topic of “Provenance Research and Photography” on April 18th and 19th, 2024 in Leipzig.

Literature recommendations

- Udo Andraschke und Sarah Wagner (Hg.): Objekte im Netz. Wissenschaftliche Sammlungen im digitalen Wandel. Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2020, https://www.transcript-verlag.de/media/pdf/2d/0a/3f/oa9783839455715.pdf

- Hans Peter Hahn, Oliver Lueb, Katja Müller und Karoline Noack (Hg.): Digitalisierung ethnologischer Sammlungen. Perspektiven aus Theorie und Praxis. Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2021, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839457900

- Matthias Harbeck und Moritz Strickert: Freiwilligkeit und Zwang. Eine Diskussion im Kontext der frühen ethnologischen Fotografie. Potsdam: ZZF – Centre for Contemporary History: Visual History, 2020, https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-1928

- Matthias Harbeck und Moritz Strickert: Zeigen / Nichtzeigen. Potsdam: ZZF – Centre for Contemporary History: Visual History, 2020, https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-1927

- Jessica Heesen (Hg.): Handbuch Medien- und Informationsethik. J.B. Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart 2016, https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-476-05394-7.pdf

- Arvid Deppe: FAIR, CARE und mehr. Prinzipien für einen verantwortungsvollen Umgang mit Forschungsdaten. In: Matthias Schulze (Hg.): Historisches Erbe und zeitgemäße Informationsinfrastrukturen: Bibliotheken am Anfang des 21. Jahrhunderts. Kassel University Press, Kassel 2020, S. 299-312.

- Mark D. Wilkinson et al.: The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Scientific Data 3, 2016: 160018, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18.