Returns

How Returns are Handled

There is currently no legal basis for the appropriate handling of Cultural Goods and Collections from Colonial Contexts, nor does any agreement exist that is comparable to the Washington Principles, though the subject is repeatedly discussed at various political levels, both in Germany and other countries.

Returns have been demanded by the countries and societies of origin concerned ever since the colonial era and increasingly since the 1960s, while at the same time there has been some debate on the creation of the relevant legal framework conditions. This resulted in the UNESCO Convention of 1970, for example, though the latter does not apply retrospectively, so it does not include the peak phase of colonialism. It was not until recent years that reappraisal of the colonial past in Germany started to become the subject of broader social debate. There is still no international consensus on how to deal with the colonial legacy, and in some cases there are significant differences between the various (European) countries regarding the state of the discussion on cultural goods and collections from colonial contexts.

What is more, a very large number of countries would need to be involved in any such agreement: ever since the 15th century, almost every region of the world has been part of colonial structures, at least for a certain period of time. As such, cultural objects and collections brought to Europe originate from a variety of different acquisition contexts, each of which potentially involve specific forms of handling. Appropriate action also depends on the nature of the collection: it makes a difference whether the items are of a day-to-day character, sacred objects or zoological specimens. In addition to returns, other solutions can potentially be considered such as permanent loans, legal transfer of ownership without physical relocation, financial compensation or joint handling and research of holdings. The mortal remains of human beings have a particularly sensitive status in this connection: nowadays, these are mainly to be found in anthropological and medical-anatomical collections. Here, return with subsequent burial is almost always the only possible form of appropriate handling, providing this is desired by the society of origin.

In addition to the term “return”, the terms “restitution” and “repatriation” are also used in the debate. Given the multitude of cases and constellations, “return” has become accepted as a kind of generic term. The term “repatriation” emphasises the return of an item to its social or cultural context and is often used in the field of human remains, while the term “restitution” emphasises legal aspects such as ownership.

Prominent Examples of Returns

Returns to Namibia

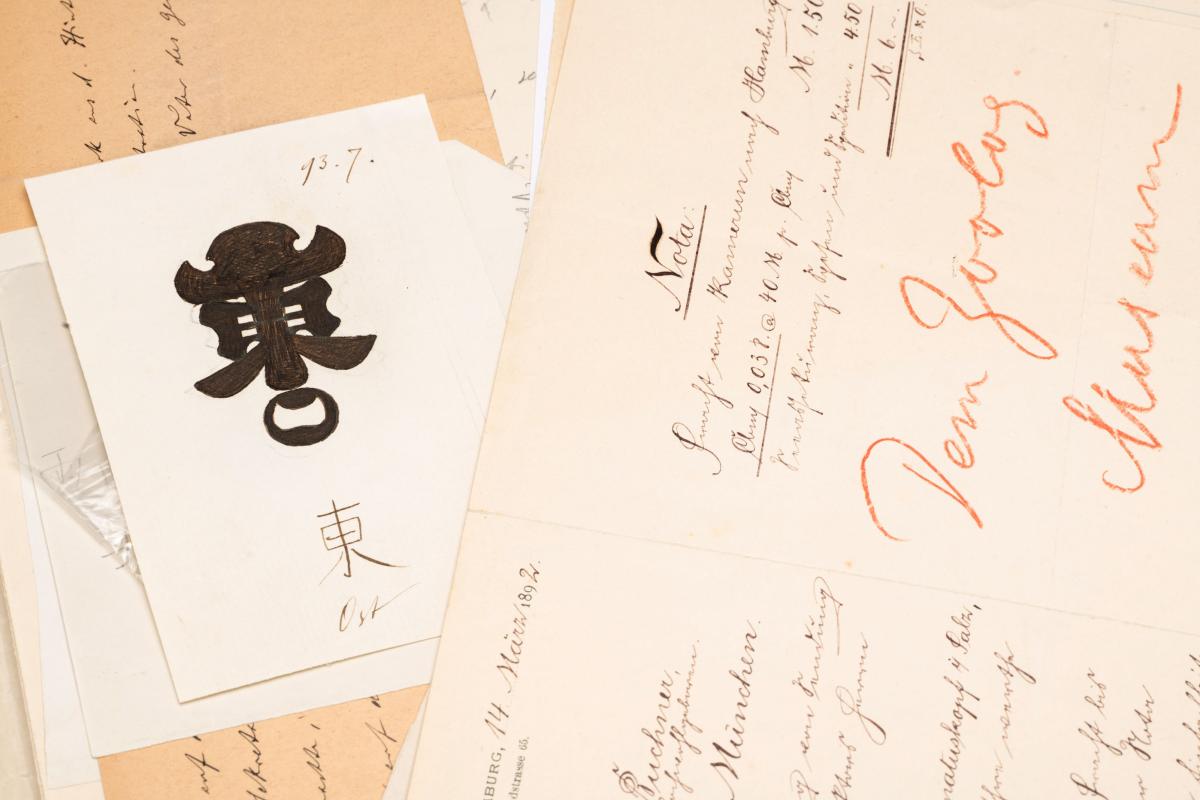

Namibia is now a key player in the debate on the return of cultural property and human remains. There have been repeated returns since the 1990s. The first, in 1996, was when the Übersee-Museum Bremen returned two books of correspondence by Hendrik Witbooi, who led the Nama resistance against the German colonial power and whose property was partly taken to German museums as war booty. The books of correspondence were included in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register and are now kept in the National Archives in Windhoek. This was followed by two private returns of books and documents to the descendants of Hendrik Witbooi.

The first return of human remains from the Berlin Charité took place in 2011, followed by further returns in 2014 and 2018. These three returns involved the remains of 82 individuals being repatriated from seven German institutions and one private collection. They had been looted from graves, among other origins, and taken from prison camps during the colonial war in Namibia (1904-1908). Since it was not possible to establish the individual identity of the bones by means of provenance research, these mortal remains have not yet been buried.

In 2019, a Bible and a whip, likewise attributed to Hendrik Witbooi, were returned from the Linden Museum in Stuttgart; they are now in the National Archives and the National Museum in Windhoek. In the same year, the German Historical Museum returned the Stone Cross of Cape Cross to Namibia, which was erected on the country’s coast by Portuguese seafarers in 1486 and taken down in 1893.

In 2022, 23 objects from the Ethnological Museum in Berlin were handed over to the National Museum in Windhoek. Other German museums are currently in talks with Namibian actors regarding the return of cultural property.

The German Lost Art Foundation supports the developments described above not only by promoting provenance research on individual objects, but also by compiling a comprehensive list of Namibian cultural property held at museums and universities in German-speaking countries and by publishing a finding aid on the subject.

Return of the “Benin bronzes” to Nigeria

The colonial occupation of the Kingdom of Benin by British troops in February 1897 marked the end of one of the most powerful West African kingdoms. One consequence was the worldwide scattering of thousands of works of art made of bronze, ivory and wood that had been looted from the royal palace. Some of these so-called Benin bronzes ended up in German museums and collections.

The first demands for these items to be returned were made as early as the 1930s. There were individual demands and negotiations in the decades that followed, but no actual returns were made. The Benin Dialogue Group was established in 2010 and involves museums in Germany, the UK, the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden working together with Nigerian partners as well as representatives of the Royal Court of Benin. It has focused primarily on scholarly cooperation.

In April 2021, at the invitation of the Minister of State for Culture and the Media, the German museums who belong to the group, the ministers of culture of the participating federal states, the City of Cologne as the body responsible for the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, and the Federal Foreign Office approved a joint declaration on the handling of the Benin bronzes in German museums and institutions. In October 2021, a German delegation visited Nigeria and a memorandum of understanding was signed stating that the first returns were to take place in the course of 2022. The “Joint Declaration on the Return of Benin Bronzes and Bilateral Museum Cooperation between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Federal Republic of Nigeria” was officially issued in July 2022. Two of the Benin bronzes were handed over at the signing itself. The process itself then got underway in December 2022 with the initial handover of 20 Benin bronzes from Berlin, Hamburg, Leipzig, Stuttgart and Cologne. Further returns are to follow.

The Foundation has been able to fund several projects dealing with the provenance of objects from the Kingdom of Benin.

For details of funded projects, see our project finder and our press releases.

Repatriation of human remains

Since 2011, the mortal remains of persons have also been returned to their descendants from German collections. Important milestones in the debate on the proper handling of human remains from colonial contexts were the publication of the “Recommendations for the Care of Human Remains in Museums and Collections” by the German Museums Association in 2013 (new revised edition of 2021), which recommends return or burial if a context of injustice exists, and the position paper issued by the Federal-Länder Commission of 2019, which attaches particular priority to the return of remains from colonial contexts. This position paper states the following: “The general willingness to return artefacts from colonial contexts, in particular human remains, to the countries and societies of origin is important for the dialogue in a spirit of partnership for which we strive. [...] Human remains from colonial contexts are to be returned.” (p. 7)

During the colonial period, the bones were usually stolen from graves or brought to Germany following military conflict, executions, imprisonment and abuse. Provenance research in this area therefore attempts not only to explore the circumstances of the relocation, but also to identify the deceased and reconstruct the circumstances of their lives and deaths (see also: Guideline for Interdisciplinary Provenance Research).

One example of such repatriation is the return of the remains of eight individuals to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (USA) by the Übersee-Museum Bremen in February 2022 [press release on the return]. In this case, the preceding provenance research was funded by the Foundation. The mortal remains probably came from burial sites and found their way to the museum from the mid-19th century onwards. For decades, Hawaiian initiatives and institutions have been trying to secure repatriation of the remains of their ancestors that were taken to various western museums. The aim is to rebury them.