Julia Rosenthal comes from a dynasty of important antiquarian booksellers – her great-grandfather Jacques (1854-1937) ran one of the most renowned antiquarian bookshops in Europe in a stately palace on Munich’s Brienner Strasse. As Jews, however, the Rosenthals suffered persecution when the National Socialists came to power: they were forced to liquidate their business, and their private art collection was among those possessions that were lost.

Jacques died in Munich in 1937; his wife Emma managed to escape at the last moment. By that time, their son Erwin had long since moved abroad along with his wife Margherita and their five children. Erwin and Margherita initially wanted to build a new life for themselves in Paris, but this plan had to be abandoned when war broke out in 1939. The couple eventually went to the USA, their Paris flat later being looted by the German occupying forces.

Their son Albi set up a new business in England and was to make a name for himself primarily as a music antiquarian. Albi Rosenthal’s antiquarian firm is now run by his daughter Julia near Oxford, representing the fifth generation of this family of antiquarian booksellers. The history of her family continues to preoccupy the 70-year-old to this day: in collaboration with the Munich Central Institute of Art History, she is doing research into the art collection lost under National Socialism and the contents of her family’s apartments in Munich and Paris through a project that is funded by the German Lost Art Foundation.

How is your research progressing?

We have come a long way with the help of the researchers in Munich. We’re very lucky to have so many documents available to us – photographs, letters, stock ledgers, even an inventory that my grandfather Erwin drew up from memory in 1957. It’s a huge operation and I’ve been trying like a mad conductor for more than twenty years to ensure all these things get to where they can be of use to research. My family is scattered all over the diaspora, you see – in America, Israel, England ...

The starting point was Munich, where several Rosenthals ran antiquarian bookshops. What memories did your father Albi have of his childhood in Munich?

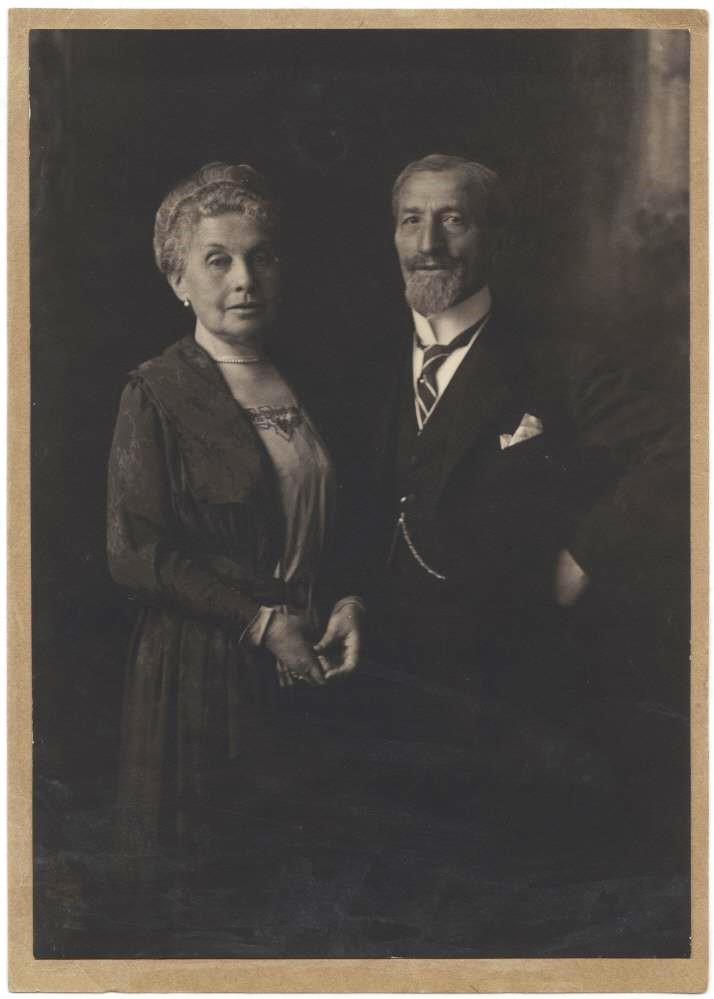

He had some wonderful memories. The Rosenthals had the beautiful building on Brienner Strasse: the rare book and manuscript showroom was downstairs, then came the apartment of my great-grandparents Emma and Jacques, above that the apartment where my grandparents Erwin and Margherita lived with the children, and finally the servants – each floor had its own identity. My father told some nice anecdotes from that period. One Sunday he went with his nanny to the park where music was playing. He was so in awe of the instruments that he trembled as he stroked them – at the age of seven he wanted a violin. As a three-year-old, he burst into tears and was inconsolable because he’d seen a snail with a broken shell. I always say that his whole life’s purpose was making it up to that snail. From the age of ten, he fervently wanted to become an Englishman, because for him England was the centre of all values – something that he saw very early on as disappearing in Germany. It was emblematic of freedom. Albi had a very broad education and was of course very much defined by his European roots. When my grandmother got stuck in the lift, she used to quote Dante by heart. I chose my ancestors very carefully.

So your family were respected members of Munich society until the National Socialists came to power ...

Yes, very much so, but then in 1935 my grandfather Erwin had to liquidate the entire company with its enormous stock of items within four weeks. I’m still in contact with the son of Hans Koch, the employee who took over. The whole thing was in the name of “Aryanisation” of course, but Mr. Koch wanted to keep the name of Rosenthal, which was rare. Almost the entire immediate family was already safely abroad by that time. Jacques died in Munich in 1937, and his wife Emma’s last years were extremely tragic. Firstly, she lost her husband – and then she had to look on while all her beautiful possessions were auctioned off at Weinmüller. She suffered greatly, not least because of being taxed under the Jewish Capital Levy and the Reich Flight Tax. Having lost everything already, that added insult to injury. She was very worried about her grandchildren and children.

In addition to the business in Munich, your family also lost their private art collection, the contents of the house in Brienner Strasse and of their later apartment in Paris. The project you’ve been pursuing since 2020 has focused on investigating the whereabouts of all these items. How did you start your search?

There was a major Rosenthal exhibition at the Jewish Museum in Munich back in 2002. After that I gave more and more documents to the Munich City Archive, which has now taken charge of an enormous Rosenthal estate. The impetus for the project with the German Lost Art Foundation was a book published in 1914: my grandfather Erwin compiled this small catalogue of his private art collection for his father Jacques’ 60th birthday as a token of his love as a son, as a tribute to the art history milieu, and also in recognition of his father’s love that had had such a profound influence on him. One of these paintings was consigned to Sotheby’s about five years ago from the estate of a collector, attributed to Crivelli. We were able to postpone the sale for a few years because we wanted to carry out solid, thorough research on this painting, and in the end we came to an agreement. As a result of this I got to meet Franziska Eschenbach of the Central Institute of Art History: I brought my great-grandfather’s anniversary catalogue along with me to Munich and we saw that there were other treasures in there as well. Then we thought we should extend the search – and fortunately we were already in contact with your Foundation. I think it’s wonderful that such projects can receive funding and I’m deeply impressed by the development of provenance research, considering it was still only a recently established discipline just a few years ago.

Do you now have a good general idea of what is still lost?

We know quite a lot about the art in general, but there is still a lot to discover regarding the furniture, tapestry and everything else. Among other things, there’s a lost collection of books and prints that we still know very little about. I don’t have an exact figure of how many objects we got back, but I have two beautiful oil paintings with portraits of Emma’s parents hanging in my home, for example, and I also have Emma’s music cabinet – she was absolutely delighted that her grandson Albi was able to carry on her passion for music. So I have my “Munich corner” at home. But the restitution issues are complicated. We were dealers and a lot of things were sold under pressure. That was clearly incorrect, but we also had the company in Switzerland and colleagues where things were left in trust, on deposit or on commission. Distinguishing all these nuances for every item is very difficult, not least because in this profession there’s a particular deep sense of loyalty among colleagues. What is more, the names of the artists keep changing. A new one crops up every ten years – it’s like Elizabeth Taylor’s husbands!

You mean it can be difficult to establish the identity of a work because there are changes in the artist it is attributed to?

Yes. What is more, I see no advantage in taking items of no great value that have been in institutions since the 1930s and now belong to important collections, and then divide them up among nine heirs. Of course there are other very valuable paintings in private ownership, such as the Cranachs, but you can hardly get access to those. I think auction houses have a great duty of care here. Until recently, they were very amateurish – only interested in making a quick profit and not wanting to invest the time it takes to spend two years researching each item. They do it better today than they used to – they have to take the time now. One can only hope that if anything does come to light again, it will be handled with greater care than before.

Your close family members lost a lot but they were all able to escape abroad. How did the other branch of the family fare?

Three of Jacques’ brother Ludwig’s four children died in Theresienstadt, and my cousin suffers enormously when she comes to Munich. She is much more affected by the horrors of her past. This branch of the family has good reasons not to share my enthusiasm for researching the past; they had a much harder time.

What was your father’s relationship with Germany like – and how do you yourself feel about that today?

My father Albi never wanted to go back to Germany, but as a music antiquarian he was a key figure for Germany as a cultural mediator. In the 1980s and 1990s we acquired lots of important manuscripts in various fields for German institutions. I’d like to quote my uncle Bernard, who wrote in the foreword to the book "Die Rosenthals": "Today more than ever, reconciliation is our only hope in this world.” I believe that’s truer now than ever before.

Are you the only one in your immediate family who is so interested in family history?

No, the others are very interested too, but in my case it gives me a real sense of fulfilment – I’ve always had a passion for family photographs and archives. There are some things that have accompanied me my entire life, memories of the past. But in the end we should always remember what Stefan Zweig said of his own collection: he never saw himself as the owner of the items but rather as their temporary trustee. I want the family estate to have a future, too – not just a past. To me that is an enormous obligation, as well as being a responsibility and a need.

-----------

In collaboration with the Central Institute of Art History in Munich, Julia Rosenthal has been conducting research since 2020 through a project funded by the German Lost Art Foundation with the aim of establishing the whereabouts of her family’s cultural property.

Many thanks to Franziska Eschenbach of the Central Institute of Art History and Anton Löffelmeier of Munich City Archive for their support with this article.